Multienzyme complexes are discrete and stable structures composed of enzymes associated noncovalently that catalyze two or more sequential steps of a metabolic pathway.[7]

They can be considered a step forward in the evolution of catalytic efficiency as they provide advantages that individual enzymes, even those that have achieved catalytic perfection, would not have alone.[1][12]

Contents

What advantages do they provide?

During evolution, some enzymes evolved to reach a virtual catalytic perfection, namely, for such enzymes nearly every collision with their substrate results in catalysis. Examples are:

- fumarase (EC 4.2.1.2), which catalyzes the seventh reaction of the citric acid cycle, the reversible hydration/dehydration of fumarate’s double bond to form malate;

- acetylcholinesterase (EC 3.1.1.7), which catalyses the hydrolysis of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter, to choline and acetic acid, which in turn dissociates to form an hydrogen ion and acetate;

- superoxide dismutase (EC 1.15.1.1), which catalyzes the conversion, and then the inactivation, of the highly reactive superoxide radical, (O2.-), to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and water;

- catalase (EC 1.11.1.6), which catalyzes the degradation of H2O2 to water and oxygen.

Then, the rate at which an enzymatic reaction proceeds is partly determined by the frequency with which enzymes and their substrates collide. Hence, a simple way to increase it is to increase the concentrations of enzymes and substrates. However, their concentrations cannot be high because of the enormous number of different reactions that occur within the cell. And in fact in the cells most reactants are present in micromolar concentrations (10-6 M), whereas most enzymes are present in much lower concentrations.[1][12]

So, evolution has taken different routes to increase the reaction rate, one of which has been to optimize the spatial organization of enzymes with the formation of multienzyme complexes and multifunctional enzymes, that is, structures that allow minimizing the distance that the product of a reaction must travel to reach the active site that catalyzes the subsequent step in the sequence, being active sites close to each other.[2][7] In other words, what happens is the substrate or metabolic channeling,[8][9][14] that can also occur through intramolecular channels connecting the active sites, as in the case of, among the multienzyme complexes, tryptophan synthase complex (EC 4.2.1.20),[3][4] whose tunnel was the first to be discovered, and bacterial carbamoyl phosphate synthase complex (EC 6.3.4.16).[5][13]

Metabolic channeling can increase the reaction rate, but more generally, the catalytic efficiency, in several ways, briefly described below.[8][12]

- The diffusion of substrates and products in the bulk solvent is minimized, then their dilution and decrease of concentration, too. This leads to the production of high local concentrations, even when their intracellular concentration is low. In turn this leads to an increase in the frequency of enzyme-substrate collisions.

- The time required by substrates to diffuse between successive active sites is minimized.

- The probability of side reactions is minimized.

- Chemically labile intermediates are protected from degradation by the solvent.

Another metabolic advantage of multienzyme complexes, similarly to what happens with multifunctional enzymes, is that they allow to control coordinately the catalytic activity of the enzymes that compose them. And taking into account that the enzyme that catalyzes the first reaction of a pathway is often the regulatory enzyme, it is possible to avoid:

- the synthesis of unneeded intermediates, which would be produced if the sequence of reactions were regulated downstream of the first reaction;

- the removal of metabolites from other pathways as well as a waste of energy.

Examples

From what was said above, it is not surprising that, especially in eukaryotes, the multienzyme complexes, like multifunctional enzymes, are common and involved in different metabolic pathways, both anabolic and catabolic, whereas there are few enzymes that diffuse freely in solution. Below are some examples.

2-Ketoacid dehydrogenase family

A classic example of multienzyme complexes are the three complexes belonging to the 2-ketoacid dehydrogenase family, also called 2-oxoacid dehydrogenase family, namely:

- the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC);[2]

- the branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complex (BCKDH);

- the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex, also called 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH).[2][6][7][10]

These complexes are similar both from structural and functional points of view.

For example, PDC is composed of multiple copies of three different enzymes:

- pyruvate dehydrogenase or E1 (EC 1.2.4.1);

- dihydrolipoyl transacetylase or E2 ;(EC 2.3.1.12);

- dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase or E3 (EC 1.8.1.4).

Then, PDC, both in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, has the basic E1-E2-E3 structure, a structure also found in the other two complexes.[15] Moreover, within a given species:

- dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase is identical;

- pyruvate dehydrogenase and dihydrolipoyl transacetylase are homologous.

And, although these enzymes are specific for their substrates, they use the same cofactors, namely, coenzyme A, NAD, thiamine pyrophosphate, FAD, and lipoamide.

In order to differentiate them, for the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex, and the branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex, they are indicated, respectively:

- E1p, E1o and E1b (EC 1.2.4.4);

- E3p, E3o, and E3b (EC 1.8.1.4).

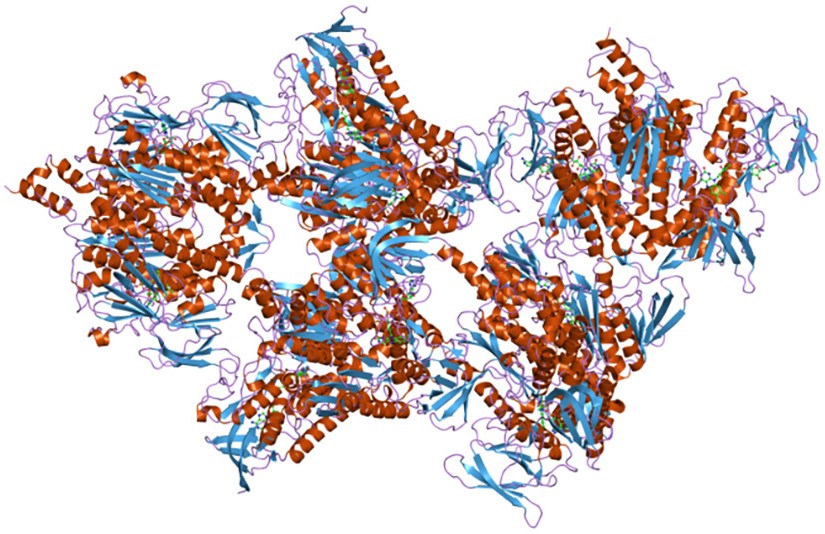

Note: the eukaryotic PDC is the largest multienzyme complex known, larger than a ribosome, and can be visualized with the electron microscope.[2]

The pyruvate dehydrogenase complex is the bridge between glycolysis and the citric acid cycle, and catalyzes the irreversible oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate, which is the conjugate base of pyruvic acid and belongs to the group of keto acids, in particular it is an alpha-ketoacid. During the reactions the carboxyl group of pyruvate is released as carbon dioxide (CO2) and the resulting acetyl group is transferred to coenzyme A to form acetyl-coenzyme A. Furthermore, two electrons are released and transferred to NAD+.

Even during the reactions catalyzed by the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex and the branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complex, respectively, the fourth reaction of the citric acid cycle, the oxidation of alpha-ketoglutarate to succinyl-CoA, and the oxidation of alpha-keto acids deriving from the catabolism of the branched-chain amino acids valine, leucine and isoleucine, it occurs:

- the release of the carboxyl group of the α-keto acid as CO2;

- the transfer of the resulting acyl group to coenzyme A to form the acyl-CoA derivatives;

- the reduction of NAD+ to NADH.

The remarkable similarity between protein structures, required cofactors and reaction mechanisms undoubtedly reflect a common evolutionary origin.

Tryptophan synthase complex

The tryptophan synthase complex is one of the best-studied examples of substrate channeling.[3][12][14] Present in bacteria and plants, but not in animals, in bacteria it is composed of two α and two β subunits associated as αβ dimers, which are considered the functional unit of the complex, in turn associated to form an αββα tetramer.[4][5][8]

The complex catalyzes the final two steps of the synthesis of tryptophan. In the first step, indole-3-glycerol phosphate undergoes an aldol cleavage, catalyzed by a lyase (EC 4.1.2.8) present on the α subunits, to yield indole and a molecule of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate. Indole then reaches the active site of the β subunit via a about 30 Å long hydrophobic tunnel that, in each αβ dimers, connects the two active sites. In the second step, in the presence of pyridoxal 5-phosphate, a condensation between indole and a serine forms tryptophan.

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) (EC 6.4.1.2), a member of the biotin-dependent carboxylase family, catalyzes the committed step of de novo synthesis of fatty acids, namely, the carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, which, in turn, serves as a donor of two-carbon units for the elongation process leading to the synthesis of palmitic acid, catalyzed by fatty acid synthase (EC 2.3.1.85).[9][11][12]

In bacteria, ACC is an multienzyme complex composed of two enzymes, biotin carboxylase (EC 6.3.4.14) and a carboxytransferase, plus a biotin carboxyl-carrier protein or BCCP.

Conversely, in mammals and birds, it is a multifunctional enzyme, as the two enzymatic activities, and BCCP, are present on the same polypeptide chain.[2]

In higher plants both forms are present.

Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase complex

Another well-characterized example of substrate channeling is the bacterial carbamoyl phosphate synthetase complex,[9][12][14] which catalyzes the synthesis of carbamoyl phosphate, needed for pyrimidine and arginine synthesis. The complex has a about 100 Å long tunnel that connects the three active sites.[13]

The first active site catalyzes the release of the amide nitrogen of glutamine as ammonium ion, that enters the tunnel and reaches the second active site where, at the expense of ATP, is combined with bicarbonate to yield carbamate, that, in the last active site, is phosphorylated to carbamoyl phosphate.

References

- ^ a b Alberts B., Johnson A., Lewis J., Morgan D., Raff M., Roberts K., Walter P. Molecular biology of the cell. 6th Edition. Garland Science, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015

- ^ a b c d e Garrett R.H., Grisham C.M. Biochemistry. 4th Edition. Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning, 2010

- ^ a b Hilario E., Caulkins B.G., Huang Y-M. M., You W., Chang C-E. A., Mueller L.J., Dunn M.F., and Fan L. Visualizing the tunnel in tryptophan synthase with crystallography: insights into a selective filter for accommodating indole and rejecting water. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016;1864(3):268-279. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.12.006

- ^ a b Hyde C.C., Ahmed S.A., Padlan E.A., Miles E.W., and Davies D.R. Three-dimensional structure of the tryptophan synthase multienzyme complex from Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem 1988;263(33):17857-17871. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)77913-7

- ^ a b Hyde C.C., Miles E.W. The tryptophan synthase multienzyme complex: exploring structure-function relationships with X-ray crystallography and mutagenesis. Nat Biotechnol 1990:8;27-32. doi:10.1038/nbt0190-27

- ^ Koolman J., Roehm K-H. Color atlas of Biochemistry. 2nd Edition. Thieme, 2005

- ^ a b c Michal G., Schomburg D. Biochemical pathways. An atlas of biochemistry and molecular biology. 2nd Edition. John Wiley J. & Sons, Inc. 2012

- ^ a b c Moran L.A., Horton H.R., Scrimgeour K.G., Perry M.D. Principles of Biochemistry. 5th Edition. Pearson, 2012

- ^ a b c Nelson D.L., Cox M.M. Lehninger. Principles of biochemistry. 6th Edition. W.H. Freeman and Company, 2012

- ^ Perham R.N., Jones D.D., Chauhan H.J., Howard MJ. Substrate channeling in 2-oxo acid dehydrogenase multienzyme complexes. Biochem Soc Trans 2002;30(2):47-51. doi:10.1042/bst0300047

- ^ Rodwell V.W., Bender D.A., Botham K.M., Kennelly P.J., Weil P.A. Harper’s illustrated biochemistry. 30th Edition. McGraw-Hill Education, 2015

- ^ a b c d e Voet D. and Voet J.D. Biochemistry. 4th Edition. John Wiley J. & Sons, Inc. 2011

- ^ a b Yon-Kahn J., Hervé G. Molecular and cellular enzymology. Springer, 2009

- ^ a b c Welch G. R., Easterby J.S. Metabolic channeling versus free diffusion: transition-time analysis. Trends Biochem Sci 1994;19(5):193-197. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(94)90019-1

- ^ Zhou Z.H., McCarthy D.B., O’Connor C.M., Reed L.J., and J.K. Stoops. The remarkable structural and functional organization of the eukaryotic pyruvate dehydrogenase complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98(26):14802-14807. doi:10.1073/pnas.011597698